I slept like a baby. I don’t know why people use that expression to describe deep, refreshing and uninterrupted slumber; my experience of babies calls to mind continual waking in the night accompanied by crying, chewing of blankets and uncontrolled pooing. Fortunately I wasn’t teething.

I slept like a baby. I don’t know why people use that expression to describe deep, refreshing and uninterrupted slumber; my experience of babies calls to mind continual waking in the night accompanied by crying, chewing of blankets and uncontrolled pooing. Fortunately I wasn’t teething.

A different and cheerful city greeted me, as I emerged blinking into the noisy urban sunlight from my hotel. Yes, even the sunshine is noisy in Spain. The hotel turned out to be not only cheap, but quite serviceable and in an excellent location, only ten minutes walk from Seville Cathedral, and La Giralda; my first stop of the day. Well, actually a café on the Avenida de Construction was my first stop, for café con leche y una tostada, to set myself up for my first days painting. This was after all, a business trip. (I have to say that officially as I’m claiming all my expenses against tax). The Fothergills Gallery Summer Exhibition was only a couple of months away, and ‘Impressions of Spain’ had already been billed as a cornerstone of the show.

Drinking coffee outdoors in the warm morning sunshine was a treat in itself after the cold grey wet winter I had just left behind. As I was seated in contemplation, a voice called my attention. A small man stood in front of me, talking unintelligibly. He was bending forwards, offering me a wooden box with a ramp constructed on top. I thought perhaps it was a model of some Inca temple he was trying to persuade me to buy, but as I couldn’t think of a use for one I endeavoured to communicate this. As soon as I spoke he said ” Ah, Inglese! ” and then exclaimed “Shoeshine!” and burst out laughing, repeating the word again, as if it was a joke he’d just been told. I tried to smile and shrug him off but he was most insistent. Oh what the hell, they were dusty after the previous nights tramping, and my shoes did have a long road ahead this week. I assented, and he proceeded with a most elaborate ritual.

With my left foot placed on the ramp of the Inca temple, first the laces were tucked in, then some shoehorn-type pieces were inserted in the top of the shoe to protect my socks. A huge shoe brush was produced which danced around my foot with great panache, as a sort of preamble. He then unscrewed the top from a bottle and poured some reddish-brown liquid on to a small mop brush with a long handle ( I would have paid good money for that brush). Thereafter a massaging operation began which will remain one of my life’s great experiences. Lovingly the liquid was applied, and all the while in Spanish he was trying to explain to me about his large family – nueve bambini – nine children, and other stuff, which passed me by. The polish had to dry, before the procedure was repeated on the other foot. In between each part, he would make an announcement, as though describing the stages of a Zen tea ceremony. Finally, the big brush returned, and with a vigour that surprised me for his age, he burnished my shoes to a gloss that I could have shaved in the reflection of. The production of a cloth at the end seemed superfluous, but allowed him a few more theatrical flourishes of the hand that I would not have missed. Finally, he announced once again “Shoeshine!” and I could have burst into applause. “Quanto es?” I asked. “Mille” he replied. “Mille?- that’s a thousand pesetas, why that’s four quid.” He shrugged and held up eight fingers and a thumb- “nueve bambini”- he repeated. I handed over the money. “Cigarrerra?” he asked. I’d have given him anything. I opened my tin of small cigars and he took one seeming delighted. Lighting one for myself as well, I reflected that I had paid more and got less from an evening at the theatre before now.

* * *

One of the problems with a painting trip is that there are usually far more subjects to paint than one could ever sketch or deal with in the given period, and consequently it can be hard to settle to one view in favour of another. The previous year, in Venice, I had decided against climbing the Campanile in St. Mark’s Square (as, alas, sightseeing has so often to be sacrificed for sketching time), assuming that there would not be a paintable view from the top apart from a dense jumble of rooftops. Subsequently I saw a fabulous line drawing of the view stretching across the lagoon, in a book of paintings of Venice, and kicked myself for dismissing it.

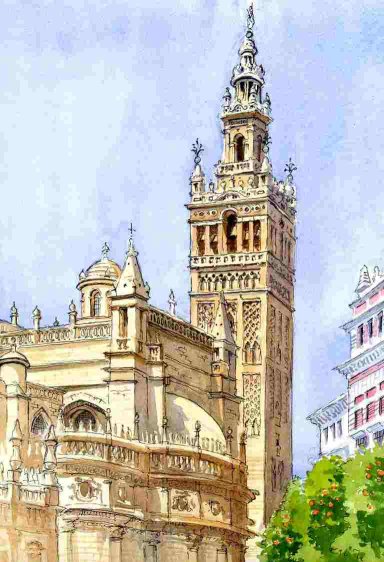

Thus, in Seville, I had determined to visit the top of the tower adjoining the Cathedral, known as La Giralda. Almost a hundred metres tall, its exterior is highly decorated with Moorish ornaments, fine arches and delicate arabesques. A perfect fusion of Christian and Muslim inspiration, it has become a symbol of Seville, and deservedly appears on postcards, thimbles and T-shirts throughout the city. A classic view of it, from the walls of the adjacent Alcazar fortress must have been painted a thousand times before, by a thousand different artists, but I wasn’t going to miss out; I’d come all this way and now it was my turn. I settled down in a shady spot and, in typical English fashion, painted my way through the Siesta period of the day.

‘How do you know when a painting is finished?’ I am sometimes asked. With a watercolour, it’s usually when it suddenly starts getting worse and not better every time you touch it. Then there’s nothing more you can do with it, even if you don’t like it, except perhaps sell it. In this case I became bored with my staring at my efforts. “TIREDNESS KILLS PAINTINGS, TAKE A BREAK” appeared on a motorway sign in my brain, so I packed up and wandered off for refreshment. Too hot for lunch, so I had an ice-cream (why do they taste so good in hot countries?), and then decided it was time to sample the view from the top of the Giralda.